Multiplicity describes a form of dissociation that happens in the area of identity. Dissociation can happen in many different areas, of which identity is one.

To start with a broader understanding of dissociation read About Dissociation. Dissociation describes a disconnection of some kind. Disconnection in the area of identity can occur in a very mild and commonly experienced way, or be quite extensive and severe. We tend to think of multiplicity as being a distinct category of its own, something you either have, or don’t have. Dissociation occurs in degrees of severity in any area, including identity.

People also often use the diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) as a shorthand term for the concept of multiplicity. DID describes very high levels of dissociation in the areas of both identity and memory. It is possible to experience multiplicity without memory loss (in fact, this is sometimes part of the goal of therapy for people who have DID) and people with that experience may instead be given the diagnosis of Dissociative Disorder not otherwise specified (DDnos). People with multiplicity issues may also be diagnosed as schizophrenic, psychotic, or other conditions, or not given any diagnosis or framework to make sense of their experiences.

Right down the ‘normal’ end of this spectrum, we all have ‘parts’ if you want to look at things that way.

We all play different roles in different areas of our lives. We show different sides of ourselves in different relationships – with our co-workers, our friends, and our children. Some theories of personality and identity development now conceive of the idea that everybody is an integrated network of sub-personalities, united by a single sense of consciousness. So, to a certain extent, we can all relate to the concept of multiplicity. We know what it feels like to be in two minds about something, to have conflict between aspects of ourselves “Part of me wants to go out tonight, and part of me wants to stay home.” We may also have experienced spending time with a new friend, who bring out a side of ourselves we hadn’t known was there. We may feel like we leave parts of ourselves behind – perhaps the part that loves to study and research is left behind as we throw ourselves into parenthood, or our fun and silly part is forgotten about as we try to manage a large company. We may also recover and reconnect with these parts later in life. All of these parts are ‘us’; they are all facets of a single, whole personality, and there is a high degree of connection and cohesion between these parts.

In multiplicity, there are dissociative barriers between these parts, like walls that disconnect them from each and keep them separate. The degree of multiplicity is determined by the extent of this disconnection. So, what are some ways multiplicity might present?

The Doubled Self

This is a really common form of mild multiplicity, particularly for people who have come through some kind of trauma. People talk about ‘the me that’s talking to you now’ and ‘the me that went through that’. They are both the same person, there is a single sense of consciousness and a unified self. There can be a sense of living in two worlds, and that even when the trauma is over, part of them is still stuck in the trauma world. For example, some people describe themselves as having been ‘the day child and the night child’. This is not DID and does not necessarily mean you have a mental illness or need to feel worried. It’s a common form of disconnection.

Rational-Emotional Split

Another really common mild form of dissociation in identity, people can experience a disconnection between their ‘mind’ and ‘heart’. For example, they can remember the facts, dates, information about a traumatic event, or they can feel the emotions associated with it, but not both at the same time. Depending on how this presents, it may be dissociation in the area of emotion, but where it is associated with feeling like there are two distinct parts of you then it may be more useful to consider it a form of mild dissociation in the area of identity.

Like all forms of dissociation, these are not necessarily pathological. In fact some therapeutic interventions, such as the mindfulness approach of developing the ‘observing self’ may be conceived of as a form of mild functional multiplicity that supports and enhances people’s ability to gain useful perspective on themselves and their situation.

My Voices

Some people who hear voices understand their voices as being parts. This is particularly so when the voices have stable personalities of their own and have been heard by the person for a while. The framework of multiplicity is not appropriate or useful for all voice hearers however! There are many other ways of making sense of voices. (see Hearing Voices Links and Information for some resources) But for some people, it helps to think of their voices as parts of them-self, or parts their mind has created. For these people, their relationship with their voices is often the key to whether their voices are comforting assets or disabling and destructive. There is a common idea that how people experience voices is diagnostic; that people who hear voices in their mind have a dissociative condition, while people who hear them through their ears (as if someone else is standing behind them talking) have a psychotic condition. This would be a convenient distinction but research doesn’t support it.

Parts that Affect My Mind

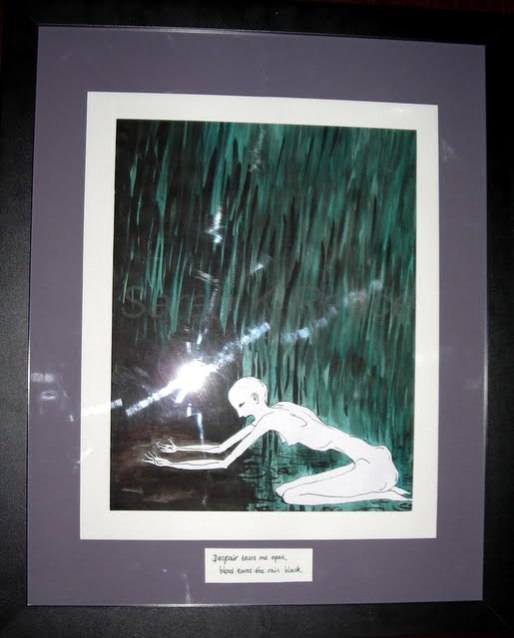

These parts have the ability to affect how someone thinks and feels. They may be able to block memories, take away words, flash images into the person’s mind, block or trigger emotions. These kinds of experiences are often considered to be part of the Schneiderian First Rank Symptoms (FRS), and to mean that the person has schizophrenia. However people who do not have schizophrenia may also experience FRS, and some research suggestions that FRS are actually more common for people who have DID than people who have schizophrenia. The person in this illustration does not have DID, as they do not switch and they do not experience amnesia (dissociation in memory). However, their experiences can be understood as being a form of multiplicity rather than psychosis. Their parts may talk to them (as voices) or be completely outside of their awareness.

Parts that Affect My Body

These parts have the capacity to affect the person’s body (another FRS). People who experience this may describe watching their own hand write in a different handwriting, or having a voice that can move their body and make them safe when they freeze in dangerous situations. This can also be really frightening and people may feel possessed and like they are fighting for control of their own body. They may or may not hear these parts as voices, and may or may not be aware of them or know what they are fighting for control with. If people interpret this experience through a spiritual framework, such as demons possessing them, they may become extremely distressed.

Co-conscious Switching

This person has a high level of multiplicity with at least one self contained, separate part that at times ‘switches’ and operates the body with complete control. Even when the other part is out, this person is still aware of what is happening, or they are filled in on what has been going on. This kind of awareness is called co-consciousness, it means there isn’t amnesia (dissociation in memory) happening for them.

Amnesiac Switching

Dissociative Identity Disorder is the diagnosis for people who experience amnesiac switching. This means that when they switch and another part is out, controlling the body and going about their day, then they are not aware of what is happening. They don’t experience themselves as switching, their perception is that they ‘lose time’ or have blackouts. Minutes, hours, days, weeks, or even years may go by without them knowing what is going on. When they come back out they may discover they’re wearing clothes they would never choose, or that major life changes – house, job, partner, have happened while they were gone.

Where there is more than one other part in a system, there may be different levels of awareness and multiplicity between the parts. For example, imagine a multiple with four parts, Greg, Graham, Greg 2, and Pearl. Greg is amnesiac when Greg 2 or Pearl are out, Pearl is amnesiac for everyone else and doesn’t know she has parts, but Greg 2 is aware of everyone and what is happening all the time. Graham never comes out, he is a part that speaks to Greg or Greg 2, but he doesn’t know about Pearl and Pearl can’t hear him. These things may not be fixed either, perhaps if Pearl was in a situation of terrible danger she might suddenly be able to hear Graham telling her to run to safety. Over time things can change.

Some multiples are in fact highly fluid, with such constant changes that system mapping is impossible and pointless until some degree of stability has been created. On the other hand, some multiples are so fixed that they find their parts are all playing roles and trying to manage people and circumstances that have long since changed. The best functioning – as with all people – seems to be a balance between flexibility (adaptation, growth) and stability.

As with all other psychological symptoms, different things can cause them, including physical illnesses and problems. If you suddenly develop parts or any other form of dissociation it is important not to presume that a psychological process is always at work. Symptoms may in fact be due to an infection or kidney problems for example.

Multiplicity can be both under, over, and misdiagnosed, as with all psychological conditions. There are other psychological processes that can seem similar to multiplicity – such as rapid cycling Bipolar, (where mood changes may be mistaken for different parts) or chronic identity instability as part of Borderline Personality Disorder (where the issue is more a disconnection from a sense of coherent self rather than the division of the self into parts). People who have a high level of adaptation to different environments may seem to ‘change personalities’ in different situations but this relates more to issues around ego boundaries rather than a divided self. Other forms of dissociation can be mistaken for multiplicity, such as when people experience severe levels of amnesia and it is assumed that this must mean that another part has been out, whereas they may not have any multiplicity at all, only memory issues. Ego states are a way of describing ‘normal parts’ and sometimes these will be mistaken for DID when inexperienced people think that feeling like a child again when you’re around your parents, for example, means that you are a multiple. Multiplicity is only one framework among many, if it doesn’t fit or isn’t helping, keep looking. There are many other ways of understanding your experiences, spiritual, social, mood related, biological, and so on. It is also possible that more than one thing is going on, for example you may have multiplicity and bipolar. In that case bipolar symptoms may occur across all your parts, or perhaps only 2 parts have bipolar and the rest do not.

It is really common for people struggling with multiplicity issues to be given many different diagnoses and spend many years in the mental health system before somebody considers dissociation as a possibility. A lack of training and awareness about these issues, as well as sensationalism and controversy have unnecessarily clouded this field and made life a lot more difficult for many people. People with parts are not more special than anyone else, and although multiplicity can seem startling at first, it is really no stranger than the experiences of people who have psychotic episodes, mania, or compulsions. There is a high level of stigma and freak factor around multiplicity that can cause a lot of problems for people who experience this and can make it very difficult to think clearly about. If you’re trying to work this out it can be tough, hang in there and be nice to yourself. You may it helpful to read How do I know I’m multiple?

Whatever is going on for you, there is hope for recovery. What that looks like is different for different people, rather the way it is for voice hearers – when ‘well’ some don’t hear voices any more, other still hear voices but they are positive, others still hear difficult voices but have learned to manage them. Some multiples work on improving communication between parts to be more of a team, or rebuilding connections to function in a less divided way. Some people integrate, where the dissociative barriers come down so that every part is ‘out’ all the time. There’s tremendous variety, and it’s important to note that the degree of multiplicity is not necessarily indicative of loss of functioning. A person with very high levels of multiplicity may function better than someone with none at all. A disability model may fit better than the medical ‘mental illness’ framework, where multiples may live differently to other people but are part of the diversity of human experience rather than ‘sick’ or ‘impaired’. Having said that, for many people dissociation of any form can be extremely challenging, distressing, and disabling. There is tremendous need for more information and support to help people with these experiences to manage them the best they can.

You can find some more information I’ve written here at Multiplicity Links, or over at the website of the Dissociative Initiative. Good luck and take care.